I believe that the moment of freedom is that between the stimulus and the response.

If there is one thing that traveling has taught me, it’s that very often the only control you have over your daily life is how you react to what is done to you and around you. Indeed, because you are an outsider, and therefore without internal cultural context, it is the way you look and your choices that define who you are, far more than your history, experience or abilities.

For example, my experiences in Japan, Ecuador, New Zealand, Cambodia and even Papua New Guinea all had much in common, in the fact that I always had a different name. In Japan I was a gaijin, in Ecuador a gringa, in New Zealand a yankee, in Cambodia a barang and Papua New Guinea a misis. In Japan I was too direct, in Ecuador I was too punctual, in New Zealand I used too much water washing the soap off the dishes (they like to leave the soap on after washing) and in Papua New Guinea, well, I’m sure I would have probably carried my spear incorrectly, leading indubitably to mortal wounds in hand-to-hand combat with my enemies.

Without fail, each culture I’ve encountered has encountered me back. This is what is sometimes surprising about being an outsider – the lack of anonymity. It can be a blessing or a curse. If the people you encounter want something from you – your money or English conversation practice, for example, you can feel quite popular. Never-the-less, this is in essence a surface relationship. As I told the child counselor when I was 9 years old – if we weren’t paying you, you wouldn’t be here.

It is, however, a reasonably honest relationship. I gain an enhanced knowledge of the world, myself and the privileges I enjoy as a western woman, and they get five dollars for a tuk tuk ride.

Of course, as you spend more time in a place, you make real friends, and that is where you learn the most. Indeed, these are the relationships that tide you over when you get tired of your newfound fame.

Again and again, on a daily basis, I am reminded of the moment of choice I have when I decide how to respond. When the ladies in the market tell me my size 10-12 frame is far too fat for any of their clothes, I can shoot off a nasty retort such as “Oh yeah? Well you’re more likely to die in childbirth!” OR, I can smile and say “Well thank you. I am quite fat aren’t I?” And we can all have a good laugh about that.

It’s the same as when I was in Japan and the people in my town would stand at the end of the aisle and whisper about the gaijin (outsider) at the end of the aisle buying her tofu. The higher ground is always to learn a funny phrase in their language… for example “Japanese tofu is the best, isn’t it?” (Nihon dofu ichiban ii desu ne?) Which would inevitably lead to laughter and potential friends, or you could say under your breath “Jeez, I wish you would shut up while I’m buying my tofu….” (urusai, ne?).

I’m not saying that I’ve always taken the higher ground. In fact, some of my knee-jerk reactions have embarrassed both myself and others. But I’m learning, albeit slowly.

When I have nothing left in a situation that I can control, I can always control my own speech and actions. I can put my intentions in check and try to remain positive and open, forgiving them for they know not what they do. Or, I can revert to feeling like an 8 year-old under attack from the other girls in class and revert to self-preservation and self-defense.

In many countries in Southeast Asia – such as Cambodia – it’s the short same split-second of freedom when making moral and ethical decisions. A man with one eye, a missing limb and a sad face approaches you when you’re climbing into a tuk-tuk asking for money. Do you give it to him? This morning I didn’t, I politely declined and he wandered back off down the street muttering about the bitch barang who couldn’t even spare a dollar for his sorry ass self.

Should I have given him some money… I dunno. Probably. How about the children who beg late into the night outside restaurants? How about the vendor who charges you double what you should pay for a mango? Where is the line? And how much does it really matter? When are you being taken advantage of, and when is the reality much more complicated, that perhaps by your mere presence, you are in some way taking advantage of them?

It’s not always possible to assume best intentions. Because, in the end, most people don’t have best intentions in mind for you. Their own moral and ethical code, perhaps their religion, the lessons their families taught them, or their own greater need guide their actions as surely as your own. That said, how much more negative energy is created in this world by distrust, anger and self-preservation. How shall we find a balance between acting like a fool and putting yourself in a self-defensive cage?

Additionally, I realize that in Asia I am treated better than some travelers because I am white and western. The only other thing better would be if I were a white, western male. A few weeks ago, I went to dinner with a friend in Siem Reap who is American, with parents from Nigeria and Jamaica. We were treated abhorrently. Gone were the kind smiles from the waitresses and the attentive questions of “you need something lady?” from the shop owners. We were quite literally glared at with a mistrust I had not yet overtly experienced in Cambodia. Granted the people we met did not grab their hair and say “Africa! Africa!” at us, the way they did to some visiting children a friend was guiding a few weeks ago, but the responses were chilly at best.

Now I am no idiot. I was born in Cincinnati, Ohio and therefore recognize the aspects of racial privilege at home as well, but here was a surprisingly overt show of racism that I had not seen since Japan.

And what was I to do? When it came up in conversation later, I asked, “does it bother you, that you are treated differently here?” “I try not to think about it, he said, because it would drive me crazy.” In all honestly, it's probably no worse than at home, just more overt.

And so, here is an example of a choice as well. One I am privileged not to have to make, much like many of the choices my Asian female counterparts must make everyday. And yet, I have only the ability to bear witness, and to recognize my privilege.

I’m not sure I know the answers to these questions, but as my last day in Cambodia comes to a close, these are the thoughts that run through my mind.

The last few weeks were spent in Siem Reap finishing up classes with my Cambodian students, saying goodbye to friends, both Cambodian and Western, 4th of July parties (held at a British friend’s house, with plenty of jokes about slinging tea:-), and, this morning, a visit to Tuol Sleng prison (S-21) in Phnom Penh before a late afternoon flight out to Bangkok en route to Nepal, the next leg of the journey.

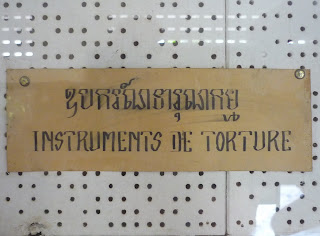

My hostel here is Phnom Penh is right across the road from the infamous Tuol Sleng prison, a former school turned gory torture chamber during the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979. Yesterday I sat beneath the leafy canopy of the flower garden at the hostel restaurant sipping my coffee and gazing across the road at the gate to the infamous school/prison. And, this morning, after a continental breakfast amid the bougainvillea, I took a deep breath, donned my dark glasses and crossed the road to wander through the classrooms and gaze into the eyes of the photographs of the 20,000 men, women and children killed there, so many of whom reminded me of my Cambodian students and friends.

The school looks much like any school in Cambodia, with high ceilings and open porches that lead along the edge of the buildings connecting the classrooms. And yet, what is seen there is so different than what should be found in a school. Photos of those killed peer out at you pleadingly. “Please, let me be spared” they say. In the end, almost none were spared. Of the 17,000 imprisoned, only 12 survivors are recorded.

The beds that the final tortured and bloated bodies were found on when the Vietnamese troops arrived remain intact, with gruesome photos of the scene upon arrival hanging at their head. Nothing is left to the imagination. All is documented painstakingly.

I’ve been to Auschwitz and the Anne Frank house and Hiroshima… and yet, somehow, I do not remember crying. But I did cry today, for those who died and for those that killed so many and stunted the growth of a nation.

All this is not to overshadow the knowledge that as an American I am not without blame in some of this situation. Many of the Cambodians that fled towards Phnom Penh and were perhaps captured were fleeing not only the brutal Khmer Rouge regime, but also the bombing in the east of the country closer to Vietnam by American troops.

So, what is one to do with all this?

I went back to my hostel, cried a bit more, packed the rest of my bags and headed off to the market to wander around before taking off to the airport and flying away from Cambodia, a choice egregiously unavailable to most Cambodians.

And so, in the end, the most I have been able to do here is to bear witness. Cambodia is a country of great strength, of great corruption, of humor, vigor, pain, suffering and also hope.

I leave hoping that as I process what I have learned here it will make me a better friend, daughter, sister, lover, mother, teacher and student.

Because I am still learning how to make momentary choices.

Below is a poem I wrote when I was 20 and living in Ecuador. I return to it sometimes to remind myself of the journey. So exciting and yet so arduous.

Quito, Ecuador. Spring 2000

I passed an indigenous woman in the street today

And I did not know her name, but I named her indigenous

And her soul flew out from behind her eyes to curse me.

I did not give her the quarter and three cents I had in my pocket,

Because I knew she would hate me,

Whether or not I gave her the money.

(And I knew I would hate myself, whether or not I gave her the money.)

She did not know me, but she named me gringa.

(A woman who walks with her legs wide open and her purse sowed up.)

What’s more, she named me American,

And I could feel the hot syllables of hate

Scribbled across my back as I

Walked and walked and

Pretended and pretended

To feel nothing.

And the change in my pocket whispered angrily

Against my thigh.

3 comments:

Jenny, thank you for sharing your journey, insight and experience. I can't wait to see you again and for all of the wisdom you will be bringing home to the United States to share with all of us.

Terrah

Very powerful post Jennie! Well written and clever...you wanna write my vows for me when the time comes?

P.S. Are you calling me an 8-year old? :P

Jennie - WOW! An inspiring and moving piece here, which makes me think lots too about life in Cambodia.

Don't worry I had a cry in the Toul Sleng Museum too. I couldn't walk round the final building because I couldn't read the stories of those involved for tears in the end.

Take care on the next step of your journey.

Post a Comment